Ghana Priorities: Gender

Technical Report

The Problem

Article 14(2) of Ghana’s Children’s Act (560) of 1998 defines child marriage as a marriage in which at least one partner is a child below the legal age of 18 years. UNICEF (2016) defines child marriage as “a formal marriage or informal union of children under the age of 18 years”. UNICEF (2016) observes that 1 in 5 girls between the ages of 20 and 24 years were married before their 18th birthday, while 1 in 20 girls marry before they turn 15 (de Groot et.al. 2018). Child marriage forces girls to assume adult responsibilities even though they are not physically, emotionally, psychologically and mentally ready for such responsibility. The result has been harmful to these girls, their children, families and the community, making it a priority to eliminate it globally.

The incidence of child marriage is high among girls, and rare among boys. Domfe and Oduro (2018) using data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey report a national incidence of 27.2% among girls. The authors also find that the incidence of child marriage is higher in rural Ghana at 34.3% compared to the urban rate of 19.4%. Furthermore, their research reveals that the incidence of child marriage is highest in the Northern Region of Ghana (38.0%). The incidence is higher among the poorest population and uneducated women (de Groot et al. 2018). Although the national incidence rate of child marriage has reduced in Ghana over time, it has increased in the regions in the northern sector, with an incidence rate of 33.6% in 2014 compared to 26.4% in 2011 (de Groot et al. 2018).

World Vision Ghana (2017) identifies the interplay of economic, structural and social factors as being the main drivers of child marriage. The World Vision Study in four regions of Ghana found that whilst teenage pregnancy was a reason why many girls in southern Ghana were married off or of lived in a consensual union with the fathers of their children, in the northern sector of the country, child marriage occurred largely because of cultural practices. For example, the practice of bride exchange involves giving a daughter away in marriage to a member of the family of her brother’s wife. Parents sometimes marry off their daughters in order to strengthen relationships between families. Poverty was found to be a causal factor among communities in the four regions where the World Vision Study was undertaken. In the Upper East Region and Northern Region, it was found that some parents would marry off their daughters in order to acquire wealth in the form of livestock.

The Constitution of Ghana and Ghana’s Children’s Act prohibit child marriage. Ghana has ratified international instruments such as the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) which contain provisions against child marriage and as the Pew Research Center (2016) reports is among many sub-Saharan African countries that have deployed policies to ban child marriage.

While these laws exist, their effectiveness is limited due to the challenges involved in enforcing them, particularly in communities where social and cultural norms are strongly adhered to. The effectiveness of these laws depends on the ability of these laws to eliminate cultural and social biases and change behavioral patterns that promote discrimination against girls.

Following from the study by Domfe and Oduro (2018), our study will focus on interventions to reduce child marriage of girls between the ages of 15 and 17 years (the high prevalence age group) who live in the five northern regions of Ghana (high prevalence regions). The interventions are non-monetary instruments which attempt to engage the complicated nexus of poverty and culture that promotes child marriage: (1) community dialogues to engage both extended families and local leaders, (2) a conditional asset transfer to girls who remain both enrolled in school and unmarried, and (3) education support in the form of school uniforms to all girls.

The assumptions, which form the basis for all the interventions, are listed below:

- The number of girls in the northern regions, between the ages of 15 and 17, is 123,946.

- The prevalence rate for adolescent marriage, ages 15-19, is 26%, the average of the northern regions (Ghana Multiple Cluster Indicator Survey, 2017/18).

- All girls, who marry, drop out of school.

- Most girls (67%), who marry before the age of 18, become pregnant before 18 (Yaya et al, 2019).

- One child is born per pregnancy.

- The dropout rate from primary to junior high school is 50.67%.

- The average age of adolescent maternal deaths is 17.

- Unless otherwise indicated, all monetary figures are reported at an 8% discount rate.

The benefits modeled are common to all the interventions and include the associated dangers of adolescent pregnancy, the increased probability of falling victim to intimate partner violence (IPV), and the income boost that comes with completed junior high school education.

The health-related benefits are based on the above assumption that most (67%) girls, who marry, become pregnant before the age of 18. The averted dangers associated with adolescent pregnancy were included as benefits in all the interventions, and their respective risk ratios are presented below.

Intervention 1: Community Dialogues

Overview

This involves educating and sensitizing children, families and communities about the negative impacts of child marriage on girls, their children and the community. Sensitization is not just for the girls but also for the parents and extended families because in most cases these girls do not have a say in the decision to get married since such decisions are made by their parents. The purpose of this intervention is to address the social norms associated with the practice of early marriage.

Implementation Considerations

The parameters associated with this intervention are based on an experiment undertaken by the Population Council in the countries of Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Ethiopia (Erulkar et al., 2017). It involves the development of a facilitator’s manual, recruitment and training of facilitators, and the organization of community dialogues over a period of two years. To enhance the effectiveness of this intervention, focus groups are formed based on age, gender and stage in life, with separate groups for adolescents and adults. Based on the experience of Hiwot in Ethiopia (Jones et al, 2016), these focus groups are targeted for peer-to-peer, mother-to-mother or house-to-house education with meetings held weekly for 16 weeks each, after which new groups made up of new community members are formed to start the discussion. The uptake rate for this intervention is 69%, resulting in the number of girls exposed to the community dialogues intervention at 63,164.

Costs and Benefits

Costs

The costs incurred in implementing this intervention are the cost of the dialogues which includes cost of recruiting facilitators and developing the facilitator’s guide. Based on Erulkar et al. (2017), the cost of community dialogues in Burkina Faso, per marriage averted was US$159 (at a prevalence rate of 24%), for a total of GHS 8.5 million. Also included among the costs of the intervention are administrative charges, which are assumed to be 1% of total costs.

Benefits

The benefits are derived from the 6,131 avoided early marriages and include the averted health conditions associated with adolescent pregnancy, of which 4,108 are delayed by the intervention: pregnancy costs, valued at GHS 892,000, maternal deaths (3), infant deaths (33), cesarean sections (526), abortions (665), and fistula (2) avoided. An additional benefit is the avoided productivity loss from intimate partner violence, to which child brides are more exposed, and which is valued at GHS 1.3 million. Finally, this intervention appeared to have no impact on girls’ school retention for the 15-17 year old group; Erulkar et al (2017) report a risk ratio of 0.99. Total benefits from the intervention are estimated at GHS 38.2 million, with the largest benefit coming from infant mortality, GHS 32.1 million.

Intervention 2: Conditional Asset Transfer

Overview

This intervention involves the transfer of an asset to the parents of girls, provided that they remain both unmarried and enrolled in school. The asset could be a sheep or any livestock that is locally relevant. In this analysis it is the equivalent to 3% of average annual income in 2019. This intervention is aimed at providing the family with an additional income source, which, it is hoped, would reduce the financial incentives associated with child marriage.

Implementation Considerations

The intervention would be implemented for three years, modeled with one cohort of girls. The asset is available to all girls who are enrolled in Junior High School and are unmarried. The girls would be required to re-enroll annually. The asset is given at the end of the successful completion of an academic year. Assuming an uptake rate of 63% as in the Erulkar (2017) paper, 57,661 girls are estimated to be exposed to the intervention. All girls eligible must be offered the asset or else the intervention may stimulate moral hazard behaviour, motivating families to remove their girls from school in order to be offered the asset.

Costs and Benefits

Costs

The costs associated with this intervention include the provision of the asset to all those eligible for three years, provided the girls remain enrolled. The asset is valued at GHS 378.6 in 2019, and the total cost of offering the conditional asset to 57,661 girls is GHS 18.75 million. The costs of JHS schooling, for those who would otherwise have dropped out after getting married, as well as the opportunity cost of going to school are valued at GHS 9 million and 9.2 million, respectively. Administrative costs of running the programme are assumed to be 1% of the total cost of the intervention.

Benefits

The benefits are derived from the 6,821 avoided early marriages and include the averted health conditions associated with adolescent pregnancy, of which 4,570 are delayed by the intervention: pregnancy costs, valued at GHS 1.2 million, maternal deaths (3), infant deaths (37), cesarean sections (585), abortions (740), and fistula (2) avoided. Another benefit is the avoided productivity loss from intimate partner violence, to which child brides are more exposed, and which is valued at GHS 947,000. Finally, there are 4,551 girls, who remain in school, for which there is a marginal increase in their lifetime earnings valued at GHS 62.5 million. The total benefits of the intervention are estimated at GHS 107.3 million, with the largest benefits emanating from the marginal income gain from having completed JHS (GHS 62.5 million) and infant deaths avoided (GHS 37.9 million).

Intervention 3: Education Support- Free School Uniforms

Overview

Ghana already implements a policy of free basic (pre-school, primary, junior and senior high) education for all children of school-going age. This means every Ghanaian child irrespective of location and gender has free access to at least high school education. In addition to the free basic education policy, the Free School Uniform Policy gives every student one uniform for the duration of school. This education support is aimed at giving each child of school age an extra uniform at the start of every academic year.

Implementation Considerations

To ensure the efficiency of the Free Education and the Free Uniform Policies in Ghana, this intervention aims at giving 123,946 girls an extra uniform at the start of each academic year. The analysis covers one cohort of girls, over three years of JHS. Although the free school uniform policy in Ghana provides a free uniform per child at the start of their education, most children will require two or more uniforms so an additional free uniform for these girls at the start of the academic year will reduce the cost to parents and increase the chances of the girls staying in school. With an assumed uptake rate of 70%, 63,959 girls are assumed to initially receive a uniform.

Costs and Benefits

Costs

The costs associated with this intervention include the cost of the uniform, GHS 75, for a total of GHS 4.12 million. The costs of JHS schooling, for those who would otherwise have dropped out after getting married, as well as the opportunity cost of going to school are valued at GHS 6.8 million and 7.0 million, respectively. Administrative costs of running the programme are assumed to be 1% of the total cost of the intervention.

Benefits

The benefits are derived from the 1,330 avoided early marriages and include the averted health conditions associated with adolescent pregnancy, of which 891 are delayed by the intervention: pregnancy costs, valued at GHS 226,000, infant deaths (7), cesarean sections (114), and abortions (144). Another benefit is the avoided productivity loss from intimate partner violence, to which child brides are more exposed, and which is valued at GHS 184,000. Finally, there are 3,471 girls, who remain in school, for which there is a marginal increase in their lifetime earnings valued at GHS 47.7 million.

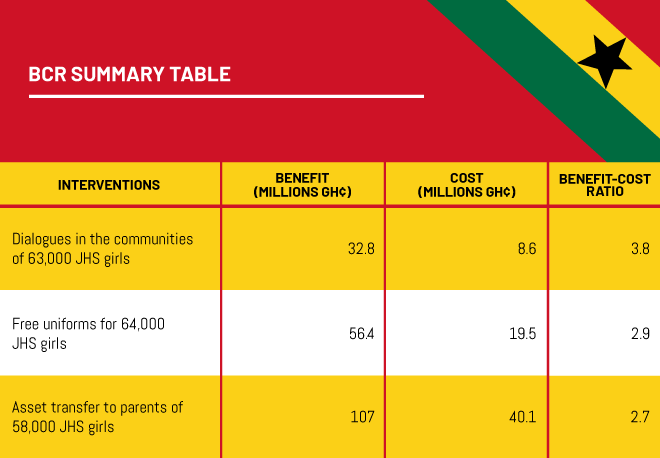

The results indicate that the Community Dialogues intervention, a relatively low-cost intervention, has the highest benefit-cost ratio (BCR) of 3.8, and is the most cost-effective policy option in the fight against child marriage. However, the Community Dialogues intervention does not have the highest overall impacts on the indicators measured: The highest number of marriages avoided, pregnancies delayed or girls who remain in school is attributable to the Conditional Asset Transfer (CAT) intervention (BCR = 2.7). Education Support is the least effective where it relates to reducing the risk of child marriage, but makes a considerable impact on girls’ school retention (BCR = 2.9).

These results provide useful information to policy makers as to the likely magnitude of costs and benefits from each of these interventions. We do not strongly endorse one intervention over another, given the relative similarity of the BCRs and the uncertainty of the evidence (drawn from three African countries not including Ghana). We recommend the Ghanaian government, should they wish to implement these interventions, conduct initial pilots with a strong monitoring evaluation element to determine the extent to which the on-the-ground reality confirms to the modeling documented in this paper.